Wits audience fascinated by first mission of its kind to Jupiter

- Wits University

South African-born space physicist Professor Michele Dougherty is a principal investigator on the Juice mission to Jupiter.

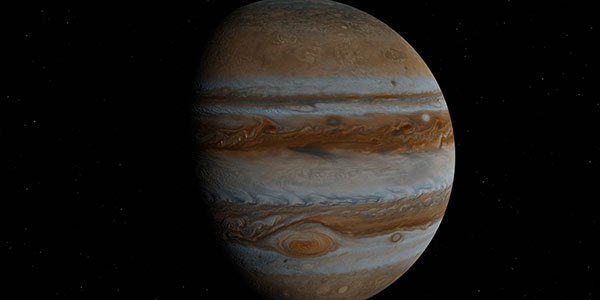

The launch of the Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (Juice) on 14 April marked the countdown for the European spacecraft as it makes its way towards Jupiter to collect data from three moons that orbit the largest planet in the solar system.

It will be a seven-and-a-half-year journey for the European Space Agency (ESA) spacecraft after it launched from the Guiana Space Centre in French Guiana on an Ariane 5 rocket. Juice is expected to arrive at Jupiter in December 2031 and it will get there by relying on gravitational assist – a kind of gravity slingshot from Earth, the moon and Venus.

This space mission marks the first time a spacecraft will be orbiting a moon other than our own. Juice will orbit the gas giant for three years with 35 flybys of Jupiter’s three biggest icy moons of Europa, Ganymede and Callisto during that time. At the end of that phase, Juice is then set to orbit the largest of the three moons, Ganymede.

The tests it will conduct on this massive moon, which is bigger than Pluto and Mercury, will include measurements of the depths of the salty subterranean oceans on the moon and to assess its composition and potential to support life. Juice will also do surface composition mapping of Ganymede looking for evidence of space weathering, cryovolcanism, so-called ice volcanoes, and tectonics on its ice shell that is thought to be 130km thick. The work on Ganymede will be aligned with the research on the two other Jupiter moons targeted in this mission so that there is strong comparative data.

South African-born Michele Dougherty is a Royal Society Research Professor and head of department of the physics department at Imperial College London. She was a key member of the Cassini space mission that was launched in 1997 and principal investigator for the magnetometer aboard that mission. Cassini orbited Saturn and discovered active icy plumes on Saturn’s moon Enceladus.

Dougherty was in South Africa this June and spent time at Wits giving two public lectures on her research. She says the clues from what they found in the Enceladus plume reinforced the argument to the European Space Agency to look to exploration of Jupiter’s moons as the mostly likely sites for potential habitability.

“We knew [from Cassini] that there was water vapour because we found that. There was also methane, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide. But most importantly, that was simple and complex organic material. So you have the three key ingredients of water, a heat source [from its core] and organic material and all three of these need to be stable,” she said.

Dougherty added: “Previous to the discoveries that we made on Jupiter and Saturn we looked for liquid water on the surface and we’ve spent a lot of time looking at Mars but we haven’t seen signs of a water sphere.

“Now we know that we can still find water but it’s not on the surface and that for me was the main driver to convince the European Space Agency that Jupiter is the place to go to to look for potential habitability,” she said.

The ESA agreed and Dougherty and her team spent nine years building the critical instrument aboard Juice, the magnetometer that’s called J-Mag.

She explained: “The way we do measurements is that if you have a conducting body embedded in a magnetic field and it’s changing; that changing field induces an electrical current that flows in the conducting body, that electrical current generates a magnetic field and my instrument is able to measure that field.”

Scientists describe Ganymede as having a metallic iron core at its centre, a spherical shell of rock surrounding the core and a spherical shell of mostly ice surrounding this rock shell. The J-Mag will do research on Ganymede’s internal magnetic and electric fields and explore how these interact with Jupiter’s magnetic field. There are known interactions as Ganymede orbits closely to Jupiter. Ganymede is also the only known moon to have its own magnetic field. This was a discovery made by the Galileo mission in 1996.

Her lecture also outlined how the J-Mag was conceptualised, built and tested over nine years. Dougherty said they were also unexpectedly forced to adapt to working remotely when Covid-19 lockdown regulations were enforced in the United Kingdom. The pandemic response meant her team had to take individual components of the J-Mag home to work on separately. But they were back in the lab three months later, she said. Their perseverance meant the long preparations phase could be completed with it all coming together finally with the launch this April.

Her instrument, the J-Mag sits at the tip of the furthest boom extension on Juice. It is 10.6 metres long and was deployed when Juice was 1.7 million kilometres away from Earth. The spacecraft is powered by an array of solar panels and has to be protected from extreme radiation and insulated for internal temperatures to stay stable. External temperatures during flybys vary dramatically. At Venus temperatures could reach 250ºC and at Jupiter it could be -230ºC.

The mission has cost the ESA $1.6 billion and at the end of its working life Juice will crash into Ganymede so it does not slam into Europa.

At the start of her talk Dougherty recalled the first time she saw the jovian moons in KwaZulu-Natal, where she grew up. She was born in Johannesburg but only lived here for the first six months of her life. She received her PhD in 1989 from the University of Natal and left South African on a scholarship in 1991.

She said: “I first saw these four large moons of Jupiter when I was a kid in Durban. Our dad built his own telescope and I remember that my sister and I helped to mix the concrete.”